Phil Marchildon

Phil Marchildon

Date and

Place of Birth:

October 13, 1913 Penetanguishene, Ontario, Canada

Died:

January 10, 1997 Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Baseball

Experience:

Major League

Position:

Pitcher

Rank:

Flying Officer

Military Unit:

433 Squadron RCAF

Area

Served:

European Theater of Operations

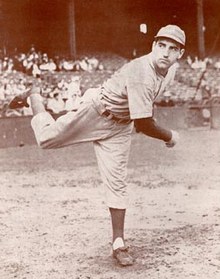

Phil

Marchildon, one of the most successful Ontario-born pitchers to

reach the major leagues, grew up in Penetanguishene, (about 200

miles northeast of London on an inlet

of southern Georgian Bay). His

major league career spanned 10 years with the Philadelphia

Athletics, but nearly came to a tragic end when he was shot down

over Germany while serving with the Royal

Canadian Air Force in August 1944.

Phil

Marchildon, one of the most successful Ontario-born pitchers to

reach the major leagues, grew up in Penetanguishene, (about 200

miles northeast of London on an inlet

of southern Georgian Bay). His

major league career spanned 10 years with the Philadelphia

Athletics, but nearly came to a tragic end when he was shot down

over Germany while serving with the Royal

Canadian Air Force in August 1944.

Marchildon, who was born on October 13, 1913, was a hard-nosed kid

who did not play baseball until high school, but quickly developed

into an excellent pitcher as well as a standout in football and

hockey at Penetang High School. In 1932, at the age of 18,

he began pitching for the Penetang Rangers, the town’s entry in the

tough North Simcoe Intermediate League. Out of an awkward, unnatural

delivery he had an overpowering fastball and a hard-breaking curve,

and led the team to repeated success. However, Penetanguishene, like

most other places in North America,

was hit hard by the Great Depression, and Marchildon needed to get a

job. Baseball certainly was not going to pay the bills, but an offer

from International Nickel, a company that operated a mine in

Creighton Mines, near Sudbury, and sponsored a baseball team in the

senior-level Nickel Belt League, meant that he could combine the

two.

Marchildon quickly became the ace of the team’s pitching staff and

remained there through the 1938 season when he set a league record

by striking out 275 batters in 25 regular season games. In July

1938, despite being 24 (a little old to be getting started in

professional baseball), Marchildon had a tryout with the Toronto

Maple Leafs of the International League. In two innings he struck

out every batter he faced and was offered a $500 signing bonus by

the Maple Leafs manager, Dan Howley.

The 5-foot-11, 190-pound right-hander joined the club the following

year (1939) but after a shaky start he was assigned to

Cornwall

of the Canadian-American League, where, over a period of 17 days, he

won six consecutive games and had an outstanding earned run average

of 1.20. He was soon back in

Torontoe

returned to and finished the year with a 5-7 won-loss record

and 4.50 ERA. In 1940, he was 10-13 with a 3.18 ERA, and earned a

late-season promotion to Connie Mack’s major league Philadelphia

Athletics. The 26-year-old made two starts for the Athletics and

lost both games but was impressive enough to join the clubs’

starting rotation the following year. Marchildon was 10-15 in 1941

for the last-placed team, then won and exceptional 17 games the

following year despite the Athletics finishing 48 games out of first

place. There was little doubt about his ability to pitch in the

major leagues, and with a better team he was a sure 20-game winner,

but the military beckoned after the 1942 season and he began more

than 30 months of service with the Royal Canadian Air Force – an

all-volunteer force.

Initially,

Marchildon trained as an aerial gunner at Souris in Manitoba. From there he

was later stationed at Trenton, Ontario, where he pitched for the Trenton Air Force team,

and was later commissioned a pilot officer with No. 2 Training

Command at Winnipeg on July 23, 1943.

He went on to graduate as a gunner with No. 3 Bombing and Gunnery

School at MacDonald, Manitoba, and was then stationed in Halifax,

Nova Scotia – where he briefly pitched for the Halifax Air Force

team - before leaving for England in August 1943.

Initially,

Marchildon trained as an aerial gunner at Souris in Manitoba. From there he

was later stationed at Trenton, Ontario, where he pitched for the Trenton Air Force team,

and was later commissioned a pilot officer with No. 2 Training

Command at Winnipeg on July 23, 1943.

He went on to graduate as a gunner with No. 3 Bombing and Gunnery

School at MacDonald, Manitoba, and was then stationed in Halifax,

Nova Scotia – where he briefly pitched for the Halifax Air Force

team - before leaving for England in August 1943.

Flying Officer Marchildon was stationed at the picturesque south

coast town of Bournemouth, when he

first arrived in

England, and it was while walking

along the main street on a Sunday afternoon that he had his first

unexpected contact with the enemy. A German fighter plane appeared

in the clear blue sky above and proceeded to strafe the street.

Marchildon scrambled for cover in a doorway as bullets tore through

the sidewalk. It was his first of numerous life-threatening close

encounters with the enemy.

Marchildon joined the 82nd Operational Training Unit at

Ossington for intensive bomber training before reporting for active

duty to 433 Squadron of the RCAF at RAF Skipton-on-Swayle in

Yorkshire. As a tail-gunner in a Handley Page Halifax

bomber, Marchildon flew night time missions that were treacherous

and uncomfortable, and in conditions that were so cold his guns

would often freeze. On one occasion, his plane returned from an

operation with 30 shrapnel holes made by enemy anti-aircraft guns,

including one that had come perilously close to the fuel tanks in

the wings.

"Some Americans went over with us one night," Marchildon recalled in

The Sporting News in July

1945, "and after that they said 'Never again at night' [all American

bomber missions were flown during the day]. In the daytime you can't

see the stuff shooting up at you. But at night, wow! It's tracers

and rockets all around that scare you to death."

Active duty offered little time for Marchildon to play baseball, but

his brother-in-law, Adam McKenzie, who played for the DeHavilland

Comets (a team based at an aircraft manufacturing plant that

featured numerous Canadians in its line-up), persuaded him to make a

handful of appearances for the team. "I only played a few games over

there and was not in very good condition to do so," he later

recalled.

His first outing against an unsuspecting U.S. Army team, however,

tells a different story. In his autobiography,

Ace, co-written with Brian

Kendall, Marchildon recounted how he threw three strikes right by

the first batter. "The poor guy hadn't lifted his bat off his

shoulder." The strikeouts continued, and one by one the American

batters returned to the bench in bewilderment, wondering who this

guy was. McKenzie finally revealed, "That's Phil Marchildon of the

Philadelphia Athletics!"

During the night of August 16, 1944, Marchildon flew his 26th

mission laying mines in

Kiel

Bay - he was four missions

away from going home and hoped to be back with the Athletics for the

1945 season. But, as the bomber flew through the darkness above the

Baltic Sea on the way to its target, it was attacked and

set ablaze by a German night fighter. The pilot immediately gave

orders for the crew to bail out but in the spiralling chaos and

confusion only the navigator and Marchildon escaped.

Stranded in the icy water of the Baltic Sea,

both crew members faced death from hyperthermia before they were

eventually picked up by a Danish fishing boat and handed over to the

German authorities. Marchildon spent the following year at Stalag

Luft III near the town of Sagan, then in Germany,

but now part of

Poland, where over 10,000 Allied

prisoners were held. Caged behind ten-foot high-barbed wire fences,

and looked upon by heavily-armed tower guards, 350 prisoners were

involved in the camp softball league in which Marchildon was a

heavy-hitting outfielder for the squad that won the camp

championship. “Looks like I’ll be missing another baseball season,”

he wrote his wife in December 1944. “We can only hope for the best

now. I, for one, am praying for the day it ends and hope it will be

soon. We seem kind of useless here and feel it deeply. We feel the

people at home do not realize our predicament as fully as they

might.”

By mid-January 1945, the advancing Russian forces were only 150

miles from Stalag Luft III. The camp was evacuated and the German

guards marched the prisoners to

Bremen. Then, as the Anglo-American forces

closed in, they were moved again. Suffering from exhaustion and

frost bite, many died along the way in what became known as the

infamous Death March. On May 2, 1945, Marchildon and his fellow

prisoners were finally liberated. "We were sleeping in a field when

I woke up suddenly and heard troops passing," he recalled. "I

thought they were Germans, but learned next day that the British had

us surrounded. Our guards stacked their guns in a building and

locked the door then surrendered to the British."

By this time, he was severely malnourished and had lost 30 pounds in

weight. He was flown back to England

to recuperate then returned to

Canada

by boat.

Nine months as a prisoner-of-war had taken its toll. He suffered

recurring nightmares, his nerves were in tatters and, not

surprisingly, he had little interest in returning to baseball. "When

I came home, my nerves came all loose," he remembered. "First night

home I took my blankets out in the yard and slept on the ground.

Couldn't sleep in a bed."

However, the persuasive Athletics' owner, Connie Mack, eventually

talked Marchildon into re-joining the team. On July 6, 1945, he

worked out with the club in

Chicago. "A new nervousness of speech and

gesture suggests something of what he went through," wrote Red Smith

in The Sporting News in

July 1945.

August 29, 1945, was Phil Marchildon Night at

Philadelphia’

Shibe Park, and the official start of his

comeback after almost three seasons away from the game. Before

19,267 fans, the obviously weak hurler was applauded during an

official ceremony before throwing two-hit ball for five innings in a

2-1 win over the Senators.

Marchildon found it difficult to focus on baseball. “I’d kind of

drift away from concentration,” he said. “I’d think about how lucky

I was to get out of it all.” He also found himself thinking

about the other five crew members who perished with the plane when

it was shot down. Marchildon didn't know of their fate until after

the war ended.

The 31-year-old made three brief appearances for the Athletics

before the 1945 season ended, but was back in full stride the

following year, winning 13 and losing 16 as the Athletics finished

in their familiar last place. In 1947, he truly regained his pre-war

form – something most onlookers thought would never happen - winning

19 games with a 3.22 ERA. “When Marchildon pitches, I might as well

leave my bat in the clubhouse,” quipped Yankees’ shortstop Phil

Rizzuto.

It was, however, to be his last shining moment in baseball. Arm

problems stopped him from ever regaining his form of the summer of

1947.

Marchildon continued to pitch in the majors until 1950, and then

played for a couple of years in the

Intercounty

League in Ontario. He went to work for A. V. Roe in Malton, Ontario, the

aviation company that produced the CF-105 Avro Arrow jet fighter, Canada's

greatest aeronautical achievement, the subsequent cancellation of

which still remains a story of political intrigue and controversy.

He then worked for Dominion Metal Wear Industries near

Toronto, and retired, aged 65, in 1978.

Phil Marchildon was inducted in Canada’s Sport Hall of Fame in 1976,

and the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame in 1983.

On July 1, 1995, he was honoured at the

Toronto Sky Dome. Throwing out the first ball, he was celebrated as

a Canadian hero for his baseball talent and for his bravery in World

War II. He passed away in Toronto on January 10, 1997, at the age of 83.

Thanks to the late

Phil Marchildon for help with his biography.

Created August 2, 2006. Updated May 1, 2009.

Copyright © 2009 Gary Bedingfield (Baseball

in Wartime). All Rights Reserved.

Phil Marchildon

Phil Marchildon Phil

Marchildon, one of the most successful Ontario-born pitchers to

reach the major leagues, grew up in Penetanguishene, (about 200

miles northeast of

Phil

Marchildon, one of the most successful Ontario-born pitchers to

reach the major leagues, grew up in Penetanguishene, (about 200

miles northeast of  Initially,

Marchildon trained as an aerial gunner at Souris in

Initially,

Marchildon trained as an aerial gunner at Souris in