Go on, why not sponsor this page for $35.00 and have your own message appear in this space. Click here for details |

Chuck Eisenmann

Chuck Eisenmann

Date and Place of Birth: October 22, 1918 Hawthorne, Wisconsin

Died: September 6, 2010 Roseburg, Oregon

Baseball Experience: Minor League

Position: Pitcher

Rank: Major

Military Unit: 827th Signal Service Battalion, US Army

Area Served: European Theater of Operations

Chuck Eisenmann is one of the most important figures in American military baseball in Europe during World War II. Founder of the top team in England in 1943 and 1944, Eisenmann then went to Paris, France, where he organized all athletic activities for Army personnel in the area.

Charles

P. “Chuck” Eisenmann was born on October 22, 1918 in Hawthorne, Wisconsin, a

community of about 1,000 in the northwest corner of the state, 20 miles

southeast of Superior.

Charles

P. “Chuck” Eisenmann was born on October 22, 1918 in Hawthorne, Wisconsin, a

community of about 1,000 in the northwest corner of the state, 20 miles

southeast of Superior.

Charles was the youngest of three brothers. His oldest brother, William, joined the Navy at 17 in 1926, and brother George also served with the peacetime Navy. Charles chose instead to join the Army, and did so as soon as he graduated from high school in 1937.

A naturally gifted athlete, Eisenmann pitched for the Eighth Field Artillery baseball team in the Schofield Barracks league at Honolulu, and was named to All-Hawaiian baseball and track teams while serving there in 1937 and 1938.

Eisenmann’s pitching talents soon attracted the attention of professional baseball scouts and it was the Detroit Tigers who first came knocking and agreed to buy him out of military service.

Eisenmann went to the Tigers’ St Petersburg, Florida, spring training camp in 1939, but hurt his arm. He was assigned to the Beaumont Exporters in the Class A1 Texas League, where he roomed with Virgil Trucks, but never appeared in a regular season game.

Later in the year, Eisenmann was assigned to the Henderson Oilers of the Class C East Texas League where he made 16 appearances and posted a 4-4 won-loss record with a 4.44 earned run average. Eisenmann finished the 1939 season with the Lake Charles Skippers of the Class D Evangeline League, making five appearances for a 1-3 record.

In January 1940, Eisenmann found himself a free agent as baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis released 91 players from the Tigers’ organization. In the opinion of Landis, these players had been kept in “cold storage” on farm teams from Shreveport to Seattle. One team with which Detroit had a secret deal was Hot Springs in the Cotton States League, which found itself left with only one player after the commissioner’s ruling.

Following his release, Eisenmann signed with the Los Angeles Angels of the Class AA Pacific Coast League (PCL). A hip injury prevented him from making the team’s roster for 1940 and he spent the season with the Vancouver Capilanos and the Yakima Pippins in the Class B Western International League. The 6-foot-1 right-hander pitched 26 games for the year and was 6-10 with a 5.66 ERA.

Eisenmann remained with Yakima for 1941 for his best pre-war season. He made 33 appearances on the mound, including 17 starts, recorded a 3.40 ERA with 12 wins and 13 losses, and led the league with 204 strike outs in 201 innings. He also beat the Oakland Oaks of the PCL, 3 to 1, in a non-league game on May 26, striking out eight.

An injury-free season had shown what the 22-year-old could do and his contract was purchased by the San Diego Padres of the PCL in November 1941. Impressed with his abilities in spring training at Imperial Valley, the Padres kept Eisenmann on their roster for the start of the 1942 season. He made his first appearance in the Pacific Coast League on April 4, throwing three innings of shutout relief in a 4-2 loss against Portland. Eisenmann was on the mound again the following day but lasted just one third of an inning in a relief role. His next appearance for San Diego was on April 9, pitching the last three innings against Seattle and allowing one run in an 11-2 loss. It was to be Eisenmann’s last game of the season as he rejoined the Army in Los Angeles on April 11, 1942.

Eisenmann attended officer training school and graduated as a second lieutenant before being sent overseas. “I got to England the latter part of ’42,” he recalls, “right in the bombings. I saw an opening in the Special Services Division so I took charge of the athletics department.”

Eisenmann was based in London with the 827th Signal Service Battalion of the Central Base Section with offices in Goodge Street, London. He wasted little time organizing their athletes into the Signal Monarchs baseball team. Among the players at his disposal were Lou Kelley, a semi-pro outfielder from Massachusetts; Bobby Korisher, a second baseman from the sandlots of Scranton, Pennsylvania; and Richard Roberts, a third baseman who played in the California industrial leagues before the war.

|

| Signal Monarchs, winners of the 1943 London International Baseball League championship. Back row, from left to right: Charles McGowan, Frank Partyka, Chuck Eisenmann, Major Bottom, Bill Stoddard, John Farrell and Craig Penrose. Front row, left to right: Joe Summerell, Fred Brandt, Bobby Korisher, Richard Roberts and Lou Kelley. |

The Monarchs entered the London International Baseball League (LIBL) in the spring of 1943 – a highly competitive eight-team circuit consisting of five US Army teams, two Canadian military clubs and a British civilian side. Eisenmann won 14 out of 16 games, 13 of them in a row, and was credited with 174 strike outs.

The Monarchs were leading the league by June and drawn in a three-game playoff with second place First Canadian General Hospital for the LIBL championship. Eisenmann pitched the Monarchs to a 4-2 victory in the first game at spacious Stamford Bridge Stadium, allowing just five hits with 19 strike outs. He clinched the championship for the Monarchs three days later with a 14-0 victory.

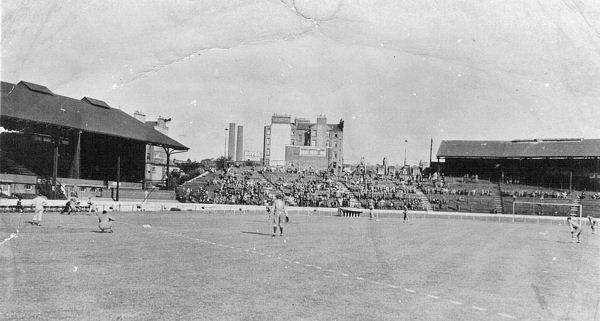

|

| Signal Monarchs playing against the First Canadian General Hospital in the London International Baseball League finals in June 1943. |

Eisenmann’s next move was to put together an all-star team to represent the US Army Central Base Section, which encompassed metropolitan London.

The CBS (Central Base Section) Clowns – as the team became known – was to be one of the most formidable service teams in Britain during WWII. Playing against military challengers as far afield as Blackpool, Liverpool and Scotland, the Clowns compiled an outstanding record of 43 wins and just 4 losses. By the end of the summer of 1943 they had defeated every top-level team in the Army, Navy and Air Force, and had successfully toured Northern Ireland. The Clowns’ line-up in 1943 included George Burns, a big first baseman from Sylacauga, Alabama; Pete Pavich, a flashy shortstop who was with the Jersey City Giants before the war; and Amey Fontana, a semi-pro pitcher from Wampum, Pennsylvania.

When asked why he named the team the Clowns, Eisenmann replies: “I had a group of guys that were characters so I just called them Clowns.”

But Eisenmann, who pitched almost every game for the Clowns in 1943, was faced with one major problem. Few, if any ball fields in Britain had a pitcher’s mound, and many games were played on soccer fields where the erection of a mound was not permitted. So, to overcome this, he set about constructing his own portable mound. Eisenmann built a wooden framework that was then layered with turf, and the unusual creation, which met all baseball regulations, journeyed everywhere with the team.

In July 1943, Eisenmann had to undergo an emergency appendectomy that robbed him of his chance to play in the highest profile baseball game staged by the American armed forces in Britain during the war. The All-Professional game between the Army and Air Force was held at London’s Wembley Stadium on August 3, 1943. Eisenmann had recovered sufficiently to help coach the Army team but was helpless to prevent the Air Force winning the game in front of 21,500 fans, on a no-hitter by airman Bill Brech, a New Jersey semi-pro.

|

| Chuck Eisenmann introducing Deputy Prime Minister Clement Atlee to the CBS Clowns at Wembley Stadium on August 3, 1943. |

In September 1943, the CBS Clowns were entered into the ETO World Series – a four-day event held at the Eighth Air Force Headquarters in Bushy Park, London, and the brainchild of Major Donald Martin, ETO Special Service athletic officer. The event included teams from all across Britain and Northern Ireland representing the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps. The Clowns were firm favorites from the outset.

In the opening game against the Signal Hounds on September 27, Eisenmann struck out 19 in the 4-2 win. The following day he defeated the Air Support Command Eagles, 7 to 1, with eight strike outs to advance the Clowns to the semi-finals. Pitching for the third successive day, Eisenmann was beaten, 3 to2, by the Fighter Command Thunderbolts to bring the Clowns’ bid for the championship to a shocking end. He had struck out 15 in the loss. Minor leaguer Mauro Duca was the winner for the Thunderbolts.

On the last day of the tournament the 116th Infantry Regiment Yankees went on to clinch the ETO World Series title with a 6-3 win over the Fighter Command Thunderbolts, while the Clowns beat the 901st Engineers, 3-0, to take third place in the tournament. Eight months later, many of the 116th Infantry Regiment players were among the first to go ashore at Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944. Pitcher Elmer Wright, centerfielder Frank Parker, and third baseman Lou Alberigo, were all killed in action that day.

In 1944, the Clowns continued their winning ways with Eisenmann at the helm. On June 3, just three days before the Normandy landings, a second Wembley Stadium baseball extravaganza was staged with the CBS Clowns taking on the Ninth Air Force. A crowd of 18,000 witnessed a combination of mastery and showmanship from Eisenmann as the Clowns blanked the Air Force, 9 to 0. Eisenmann allowed just three hits and struck out 15.

In July 1944, tragedy almost struck when Eisenmann was blown through the wall of his office in London by an exploding V1 buzz bomb. “That bomb didn’t make the slightest preliminary buzz,” he later joked, “and the only warning I had was when I heard a guard on the roof shout ‘Jump!’” he explained. “I instinctively did and was actually in the air when the explosion came. It blew me backward right through the wall of the room – fortunately, the wall was crumbling with the explosion, however.”

Eisenmann spent around seven days in hospital with an injured hip and back, and almost lost the index finger on his pitching hand. “I refused the Purple Heart,” he later joked. “I figured I wasn’t damaged enough.”

When Eisenmann resumed mound duties with the Clowns he favored the finger and used an overhand curveball release rather than his usual three-quarter style. The result was an even more effective breaking ball that was almost unhittable for his service team opponents.

Late in 1944, Eisenmann’s unit followed the Allied advance through Europe and relocated to Paris, France. One of the first things Eisenmann did was bring baseball to the liberated people of Paris. “I am astonished that in France, you do not play baseball which is, as you know, the national pastime in our country,” he told a French newspaper in late-September 1944. “We will, therefore, demonstrate the game for you.”

On Monday, October 2, 1944, Captain Eisenmann organized the first baseball game on French soil in World War II. Held at the Parc des Princes in Paris, before a crowd of 6,000, Eisenmann presented a 20-minute demonstration of the rules of the game, followed by a softball game and then a baseball game in which Eisenmann pitched the Clowns to a 3-0 victory over the US Army Polar Bears. Eisenmann also arranged many exhibitions of American sports for the Parisians like football, basketball and volleyball.

|

| Seine Section Clowns playing at Parc des Princes in Paris during 1944. |

The renamed Seine Section Clowns continued to play at the Parc des Princes with many of the existing players joining the team from London, England. One new addition to the team, however, was Lieutenant Lyn “Buck” Compton, UCLA catcher and a paratrooper with the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, whose combat exploits have recently been seen in the HBO television series “Band of Brothers.”

Compton was in Paris recovering from the trauma he had recently suffered in combat. “Lyn was one of my best friends,” says Eisenmann. “I was going on a train out to the coast and he came up to me and said, ‘I’m Lieutenant Compton, I’d like to join your organization.’ I had fictitious orders published and kept him with me for two years. Lyn was a slow talking guy, nose bent over from playing football. I had a German prisoner that did my chores and he [Compton] would follow this guy around and say to me, ‘Ask him why they shot at us when we were parachuting down,’ and the poor, terrified German would hide behind me.”

But, just as it had in 1943, the European Theater baseball crown eluded Eisenmann’s Clowns. This time it was former Pirates’ pitcher, Sam Nahem and his Oise All-Stars who knocked the Clowns out of the 1945 ETO championships in the Paris regional round. Nahem’s team went on to clinch the ETO World Series title in Nurnberg, Germany in September, defeating the powerful 71st Infantry Division (representing the Third Army) in five games.

|

| Seine Section Clowns, Paris, 1945. |

Throughout 1945, Eisenmann had taken charge of all US Army athletic activities and was promoted to the rank of major in June. He organized exhibition games for the local civilians, and oversaw the running of servicemen leagues for all sports. Eisenmann was instrumental in ensuring the American servicemen in Paris had plenty of opportunity to watch and participate in sports while eagerly awaiting their return home.

Eisenmann returned to the United States in late 1945. After four years away from the professional game he was at spring training with the San Diego Padres in 1946. His impressive assortment of pitches and undoubted athletic maturity earned the 27-year-old a spot on the Padres’ regular season pitching staff.

In his first start on April 10, in the newly classified AAA Pacific Coast League, Eisenmann beat the Los Angeles Angels, 2 to 1, allowing just five hits and striking out seven. “Eisenmann, former Army major,” wrote To McGwynne in the San Diego Tribune on April 11, 1946, “who has a fireball and a world of stuff, uncorked some dazzling mound work, and save for one shaky inning, looked like the real goods.”

A week later, on April 18, Eisenmann spoiled the Seattle Rainiers’ home opener before 13,000 fans at Sicks’ Stadium, winning 3-2 and striking out 10. But Eisenmann would only spend half the season at San Diego. A bad spell saw him lose five out of the next six decisions. In 17 games he posted a 3-6 won-loss record and a respectable 3.62 earned run average before being assigned to the Tulsa Oilers in the Class AA Texas League.

Eisenmann made 18 appearances for

Tulsa in 1946, including a 13-inning marathon against Fort Worth on September 6,

in which he lost, 3-1. He was 6-7 for the year with a superb 2.12 ERA and struck

out 82 in 102 innings.

The 28-year-old was back with San

Diego for spring training in 1947. On February 16, he made a 2-inning relief

appearance in the annual benefit game between the Minor League All-Stars and the

Major League All-Stars. The minor leaguers won the game, 6-4, in 10 innings.

After a sixth place finish in 1946,

the Padres got off to a good start in 1947, but Eisenmann suffered from bouts of

wildness. In 14 relief appearances he walked 30 batters in 31 innings. San Diego

sold him to the Memphis Chicks of the Class AA Southern Association on June 4 –

it began a three year association with the Tennessee-based team.

Eisenmann had a decent year with

Memphis under manager Jack Onslow, making 19 appearances, with an 8-5 record and

a 4.13 ERA. With his pitching under control it was only his temper that was

occasionally prone to wildness. On August 5, Eisenmann was ejected from a game

for firing the ball into the stands when umpire Frank Girard asked to inspect

it.

Eisenmann was 29 years old when the

1948 season came around, and it proved to be his best year in professional

baseball. It did not get off to a great start, however. He again pitched in the

Minors and Majors all-star game on February 15 and this time the major leaguers

won, 4 to 3, when Gene Mauch raced home from third with the decisive run on

Eisenmann’s wind-up in the eighth.

During the regular season with

Memphis Chicks, Eisenmann made 34 pitching appearances. He threw 17 complete

games, posted a 16-11 won-loss record, struck out a league second-best 152

batters and had an earned run average of 3.52. He beat New Orleans, 11-2, with a

three-hitter on May 26, was selected for the league all-star team in July, and

threw back-to-back five-hitters in August.

On September 14, in the Southern

Association’s semi-final play-offs, Eisenmann pitched 10 innings against

Birmingham and allowed six hits but lost the game, 3-2, bringing to a

disappointing end an otherwise very satisfactory minor league season.

That same month he received $250

from a Memphis packing company as runner-up player of the year, but more

importantly, he was called up to the Chicks’ parent club - the Chicago White

Sox.

A decade after starting his

professional career, not forgetting a four-year interruption that sent him six

thousand miles around the world to serve his country, Chuck Eisenmann had made

it to the major leagues. Although he never appeared in a game for the White Sox,

Eisenmann finished out the season on the bench at Comiskey Park and was still

with the team for spring training at Pasadena in 1949, when his former manager

at Memphis, Jack Onslow, became the new pilot of the White Sox.

“I really feel that I’ve acquired

the know-how and can make the grade,” he told the Superior Evening Telegram

in December 1948.

But the dream was not to be.

Eisenmann was back with Memphis for the regular season, albeit with an option to

be recalled by Chicago at any time. He had a reasonable year in 1949 but was not

able to repeat his performance of 1948. Eisenmann again made 34 appearances, he

posted a 9-13 record and had an earned run average of 5.24. And, again, he got a

September recall by the White Sox as they struggled to build their major league

pitching staff.

October 1949, signified the end of

Eisenmann’s dream of pitching in the major leagues. He was traded to the

Brooklyn Dodgers as part of the deal that brought Chico Carrasquel to the White

Sox. “Frank Lane came in as general manager [of the Chicago White Sox] from the

American Association,” recalls Eisenmann. “He brought five pitchers with him and

they’re the ones that stayed because he’s not going to be made to look a fool.

So they traded me to Brooklyn. Well, Brooklyn had about 18 starting pitchers, so

they bought me really for fodder.”

Eisenmann spent the 1950 season

with the Mobile Bears of the Southern Association. It was a miserable season for

the 31-year-old, pitching 18 games for a 2-11 record and a 3.59 ERA. He did not

win his second game until late August.

At the end of the season he was

purchased by the New York Giants and split the 1951 season between the Ottawa

Giants and the Syracuse Chiefs in the Class AAA International League. On May 13,

pitching for Ottawa, he was credited with a one-hit, 4-0, victory despite being

pulled by manager Hugh Poland after walking the first two batters in the sixth.

In 36 appearances for the season, Eisenmann was 4-7 with a 3.80 ERA.

Eisenmann remained with Syracuse at

the start of the 1952 season. He made 19 relief appearances for the Chiefs and

had an inflated ERA of 5.40 when he was sent to the Tulsa Oilers of the Class A1

Texas League, a team he had previously played for back in 1946.

He made 11 appearances for Tulsa,

pitched 22 innings and had an ERA of 3.68. One memorable performance was on

August 17, when Eisenmann pitched the last inning of a marathon 22-inning

contest against Houston, and singled in the winning run to give Tulsa a 6-5

victory. The Oilers released the 33-year-old at the end of the season.

As a free agent, Eisenmann was at

the Pacific Coast League San Francisco Seals’ spring training camp in Riverside

in February 1953. He remained with the Seals when the season started and made

three relief appearances before being released on April 10. He was picked up by

San Diego – a team he had last been linked to back in 1947 – and made a further

five appearances. On April 29, 1953, Chuck Eisenmann was released by the Padres

when PCL rosters were reduced to 21, marking the end of his professional career

as a player.

“If there had not been a war I

probably would have made the major leagues,” Eisenmann reflects. “I could throw

hard but I really didn’t know how to pitch. Today, in the major leagues you got

two or three pitching coaches. I would just blow the ball by people although I

also had a tremendous curve.”

He spent the remainder of 1953 and

the following year with the semi-pro Kearney Irishmen in the Nebraska

Independent League, where he continued to pitch well, including a 13 strike out

performance against the Holdredge Bears on June 15, 1954.

Eisenmann decided to attend the

Bill McGowan School for Umpires at Daytona Beach, Florida in 1956. He was now 37

years old and graduated from the school with a job in the California League.

Maybe umpiring was not the thing

for Eisenmann but he only lasted a single season. On June 13, 1956, he was

involved in a curious incident that took place during a Bakersfield-Modesto

game. Eisenmann - behind the plate - thought a ball had been fouled off by a

Bakersfield batter and threw another ball back to the pitcher. Meanwhile, the

runner at second headed for third because the pitch had not actually been fouled

off but had got away from the Modesto catcher. Needless to say, Eisenmann heard

a great deal of abuse from Modesto manager Al Lyons.

For the last few years, Eisenmann

had been seen everywhere with his trusted German Shepherd “London.” Before a

game at Reno with Visalia in June 1956, London performed a routine of tricks and

training to the delight of the fans. It was a sign of things to come.

Eisenmann was back on the mound in

August 1956. He joined the Bismarck Barons in the semi-pro Man-Dak League as

they made every effort to retain the pennant. Bismarck was in second place

behind the Williston Oilers when the 37-year-old Eisenmann pitched and won his

first game of the season against the Dickinson Packers on August 13. Bismarck

then advanced to the semi-final playoff series with the Minot Mallards.

Eisenmann made relief appearances in both games but the Mallards won both ending

the hopes of Bismarck advancing to the Man-Dak League finals.

The real highlight of Eisenmann’s

short career with Bismarck was his dog. “Before the game, Chuck Eisenmann sent

his German Shepherd dog ‘London’ through his paces,” wrote the Bismarck

Tribune on August 17, 1956. “The dog brought keys from Eisenmann’s car,

bowed to the crowd, brought a bat and a broom to the pitcher, ran the bases,

brought a ball bag from the mound, told how old he is (five), imitated a

kangaroo, closed a door, turned out a light, played dead, untied a boy, and did

a little typewriting.”

“The thing that really moved me

from baseball is my dog,” recalls Eisenmann. “I had a nightclub [Tobacco Rhoda’s

in North Park, San Diego] and the dog started showing signs of greatness. When I

was with San Diego and Los Angeles, instead of flying with the team I would

drive with the dog. Then Life magazine did a three-page spread, so I

moved from baseball to the dog even though I was still a pretty decent pitcher.”

London appeared in another movie in

1960, “My Dog, Buddy,” in which Eisenmann had a small acting part. Then, in

1963, came “The Littlest Hobo” television series. Another movie, “Silent

Friends,” was made in Romania in 1969. By 1971, he had four German Shepherds –

London, Venus, Raura and Hobo. “The Billion Dollar Hobo” appeared on movie

screens in 1977 and a second “The Littlest Hobo” series was launched on

television in 1979 and ran for six seasons. In all, there have been more than

160 episodes of The Littlest Hobo and London’s fame as a dog actor is probably

only exceeded by Lassie.

“They’re amazing animals,” he told

Tommy Horton of the Memphis Press-Scimitar in May 1971, “and if they just

had the physical attributes to go along with their mental capacity, one of them

might be President.”

When asked if he had formal dog

training, Eisenmann replies: “None. I never read a book [about dog training] and

now I have written four of them.”

Perhaps the most remarkable thing

about Eisenmann’s dogs is their command of the English language.

“Everything that I have done with

dogs contradicts what other people have done. I only have one dog left [this

interview was conducted in 1995] but this dog has about a 2,500 word vocabulary.

I did a lot of speaking at the psychology departments of universities because

we’re contradicting, in essence, what we’re teaching. But they only know a dog

to the conditioned stage and I start out where the dog is already conditioned

and then teach them.”

But a collision between Eisenmann’s

car and a delivery truck in 1957 almost ended London’s acting career just as it

was beginning. London suffered a broken leg and a bumped head in the collision,

prompting Eisenmann to sue the delivery firm for $35,000 in damages in 1961.

London even appeared in court in Los Angeles and demonstrated his abilities to

perform and talk. Although the court reporter refused to transcribe London’s

guttural sounds, several courtroom observers thought he said: “Hello, how are

you?”

London had no immediate comment,

however, when the jury rejected Eisenmann’s damage claim.

Chuck Eisenmann, baseball pitcher,

wartime baseball pioneer and dog

trainer extraordinaire,

passed away in Roseburg, Oregon

on September 6, 2010.

Thanks to

the late

Chuck Eisenmann, with

whom much of this information was gathered during an interview on November 6,

1995. Thanks to Bill Swank for the photo of Chuck Eisenmann with the San Diego

Padres.

Looking for

Train the

Trainer Glasgow? We deliver award-winning training for trainers

in Glasgow and Edinburgh.

Created May 23, 2006. Updated February 20,

2012. Copyright © 2018 Gary Bedingfield (Baseball

in Wartime). All Rights Reserved.