Go on, why not sponsor this page for $5.00 and have your own

message appear in this space.

Click here

for details

|

Click here for details

Steve

Sakas

Steve

Sakas

Date and Place of Birth:

May 13, 1921 Chicago, Illinois

Died: November 5, 2012 Skokie,

Illinois

Baseball Experience:

Minor League

Position:

Pitcher

Rank: Unknown

Military Unit:

119th Infantry Regiment, 30th Infantry Division US Army

Area Served:

European Theater of Operations

Steve Sakas dreamed of being a big league

pitcher. When he hurt his arm he lived his dreams through the

hundreds of youngsters he taught to pitch.

Steven

P. “Steve” Sakas was born in

Chicago,

Illinois on May 13, 1921. He was a

multi-sport athlete at Amundsen High School and attended Wright Junior College

where he struck out 15 consecutive batters in one game.

Steven

P. “Steve” Sakas was born in

Chicago,

Illinois on May 13, 1921. He was a

multi-sport athlete at Amundsen High School and attended Wright Junior College

where he struck out 15 consecutive batters in one game.

Despite interest from the Chicago White Sox, Sakas went to Western

Michigan in Kalamazoo on a baseball scholarship, but

within a year he signed with the White Sox for $75 a month and a

$500 bonus. Sakas played his rookie year with the Lubbock Hubbers of

the Class D West Texas-New Mexico League in 1941. But it wasn’t only

the beginning of a playing career, it was also the start of a

lifelong dedication to teaching others to play ball.

"I was 13 that summer," recalls Bill Cope, who was a young

ballplayer in Lubbock in 1941. "We had a

sandlot baseball league of four or five teams and played on a field

across from the old Texas Tech gymnasium. Somehow, Steve Sakas and

another Hubber, Gene Stack, learned about the games and started

coming there some afternoons when they were in town and watched and

encouraged us and gave us some pointers. We thought this was great

because these were real professionals and our idols and we were at

the ball park for just about every Hubbers' game."

The West Texas-New Mexico League was a notorious hitters’ paradise

at the time and Sakas’ 9-18 won-loss record and 4.25 ERA looks a lot

worse that it was. In 1942, he moved up to the Superior Blues of the

Class C Northern League where he was 9-12 with a 3.96 ERA.

|

|

|

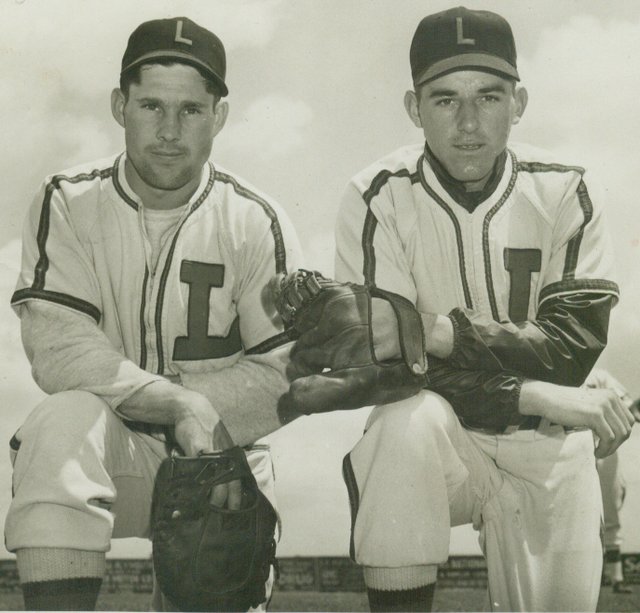

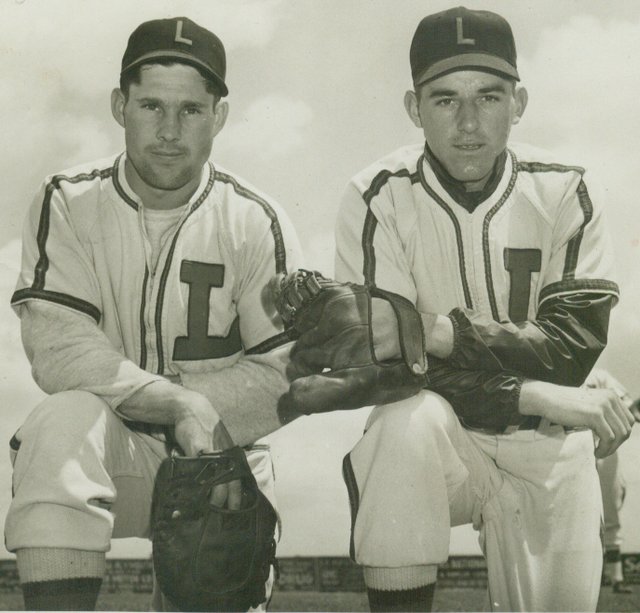

Steve Sakas (right) with the Lubbock

Hubbers in 1941. On the left is the Hubbers' first baseman

Kauzlerich.

|

Sakas was

forced to put his career on hold when he entered military service at

the end of the 1942 season. He was inducted at Fort

Sheridan, Illinois and took basic training with the Army Air Corps

at Miami Beach

as a physical instructor. Sakas was then assigned to Hammer Field, a

4th Air Force training base, near

Fresno,

California. From there he was

relocated to Ephrata Army Air Base in

Washington, where he coached the baseball

team.

|

|

|

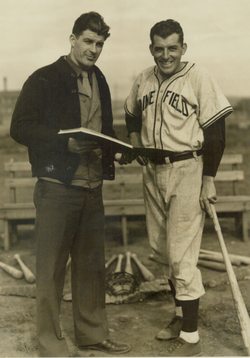

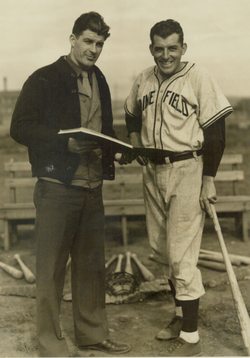

Steve Sakas (right) with Herm Reich at

Gray Field, Washington

|

As the war progressed, every able-bodied man was

needed for overseas service and Sakas quickly found himself in the

infantry. “We had a warrant officer who tried out for the baseball

team,” says Sakas. “He didn’t make the grade and I cut him from the

team, but he really got me back when he sent me to the Army. That

was the dumbest cut I ever made!”

Sakas was soon on his way to Europe aboard the Queen Elizabeth. He was briefly

attached to a replacement depot in England before being assigned to the

119th Infantry Regiment of the 30th Infantry Division. Not only did

Sakas find himself in the thick of the Battle of Bulge but he also

found out that he was the new bazooka man, even though he’d never

fired a bazooka in his life! “Do you know what beat the Germans?”

Sakas asked. “The thought of this crazy Greek coming at ‘em with a

bazooka!”

Sakas was with the 30th Division as they crossed the Rhine, then the

Ruhr, and captured Magdeburg on the Elbe

River on 17 April, 1945, where they

were forced to wait to allow the Russians to be the first in to Berlin.

Following the German surrender, Sakas got back to doing what he did

best, organizing sports and recreation for the troops, which

included a softball team. One day, Colonel Stewart asked Sakas if he

could put together a baseball team. Another division had a hot team

that included Billy Johnson of the Yankees and were looking for games.

Sakas told the Colonel he didn’t have any baseball players but he’d

do his best. He held tryouts among his softball players and selected

the best, including the company cook, who became the team’s catcher

and always ensured Sakas had the best steak whenever he wanted.

The next step was to find somewhere to play. Sakas requisitioned a

large mansion house and grounds in the German town of Schleiz,

assuring the family that his players would take great care of

everything. He then set about finding uniforms and approached a

German dress factory which just happened to be owned by the family

who owned the house his baseball team had taken over. While the

factory started making uniforms, Sakas approached a cobbler, who

made baseball spikes following the ball player’s careful

instruction. “They looked great but they must have been the heaviest

spikes in the world!” recalls Sakas.

Caps

were next on the list and Sakas had these made by a German

manufacturer who decided to use cardboard for the peak inserts.

“Just like the spikes,” says Sakas, “the caps looked great, but we

would sweat a lot and the cardboard peaks would just flop down in

our faces while we were playing.”

Caps

were next on the list and Sakas had these made by a German

manufacturer who decided to use cardboard for the peak inserts.

“Just like the spikes,” says Sakas, “the caps looked great, but we

would sweat a lot and the cardboard peaks would just flop down in

our faces while we were playing.”

Sakas was getting a dozen baseballs sent every month by Bill DeWitt,

owner of the St. Louis Browns, but balls were always in short supply,

and some German women even tried making these – the experiment was a

disaster and ended very quickly.

Dressed and ready to go, Sakas’ ball team christened their home

ground Colonel Stewart Field and played a number of games including

a heartbreaking, 1 to 0, loss to Sam Nahem’s All-Stars who went on

to be the European Theater champions. Nahem asked Sakas to come and

play for his team in Rheims,

France, but

Sakas was more interested in getting home to the States and picking

up where he left off with his baseball career.

He was back home by November 1945. “I went to spring training with

the Milwaukee Brewers in 1946,” recalls Sakas. “They felt I wasn’t

ready and sent me to Greenville, South Carolina.”

Sakas

only spent a short time with Greenville

and joined Vicksburg of the Southeastern League where he

was 5-4 with a 3.89 ERA. In 1947, he went to spring training with Shreveport of the Texas League and was assigned to Texarkana of the Big State

League for the rest of the year, where he had a career-year. Sakas

was 13-5 during the regular season and won another two games in the

playoffs. His career looked to be on the right track. He was back

with Shreveport in 1948, won his first start against Oklahoma City,

9-4, on April 29, then beat Dallas, 3-1, on May 4. But a shoulder

injury brought everything to a sudden halt. He simply couldn’t throw

without pain and held out for the rest of the season before retiring

from pro ball.

Sakas

only spent a short time with Greenville

and joined Vicksburg of the Southeastern League where he

was 5-4 with a 3.89 ERA. In 1947, he went to spring training with Shreveport of the Texas League and was assigned to Texarkana of the Big State

League for the rest of the year, where he had a career-year. Sakas

was 13-5 during the regular season and won another two games in the

playoffs. His career looked to be on the right track. He was back

with Shreveport in 1948, won his first start against Oklahoma City,

9-4, on April 29, then beat Dallas, 3-1, on May 4. But a shoulder

injury brought everything to a sudden halt. He simply couldn’t throw

without pain and held out for the rest of the season before retiring

from pro ball.

Sakas worked with his father in the family tavern business and

bought his own place on Rand Street in Des Plaines, called Steve’s

Lounge (which he owned until his retirement in 1986). In 1970, he

had the honor of having a street named after him in Des Plaines. Sakas Drive is a small street running

alongside his old bar.

|

|

|

The Texarkana pitching staff in 1947.

Sakas is second from left

|

But Sakas wasn’t through with baseball. He continued to pitch, when

his arm would allow, and hurled for the semi-pro Michigan City Cubs

of the Michigan-Indiana League in 1949. He also scouted for the White Sox and Milwaukee Brewers. In 1951, he formed

the AHEPA All-Stars, a collection of Greek-American ballplayers. The

team had great success in semi-pro leagues. Sakas was also

player-manager for the semi-pro Skokie Indians in the late 1950s and

1960s.

During the 1970s, Sakas was a pitching coach with high school and

college kids. He served as the pitching coach for the Lincolnwood

Big League All-Stars youth team which won the World Championship in

Florida

in 1973. He served as pitching coach for the Niles West Indians in

the mid-1970s when they won two AA State Championships.

During the 1980s he coached the pitching staff of the semi-pro

Maryville Shamrocks and the Barnstormers, who won the AABC Illinois

state title two years in a row.

In the late

1980s he served as pitching coach for Northeastern

University and began giving lessons at

the Grand Slam USA Baseball Academy in Palatine.

At 87 years old, he

was still

teaching pitchers to throw. He firmly believed in teaching control

and for pitchers to master the fastball, curve and change up. He

won’t teach a kid how to throw a slider or a circle change. “Those

pitches are too hard on your elbow,” said Sakas who knows too well

the devastating effects of a pitching injury.

And what about that shoulder injury he suffered

back in 1948? Well, Sakas suffered a heart attack in 1998. Talking

with his doctor one day, he mentioned how he used to play pro ball

and hurt his shoulder. The doctor offered to take a look at his

shoulder with an MRI scan and discovered that he’d torn his rotator

cuff. “At 78, is it too late to make a comeback?” Sakas wondered.

Steve Sakas lived in Skokie, Illinois and

passed away, aged 91, on November 5, 2012. Just weeks before his

death, Sakas was able to see one of his baseball students, George

Kontos, pitch for the San Francisco Giants in the 2012 World Series.

This tribute to Steve aired on WGN TV Chicago in 2013

http://landing.newsinc.com/shared/video.html?freewheel=91046&sitesection=wgn_localnews&VID=24662017#.UVr-y-VfBux.email

Thanks to the late Steve Sakas who shared this information with me during a

telephone conversation in February 2008. Thanks, also, to his sons,

Jim and Peter, for helping with additional information and photos.

Created

April 2, 2008. Updated April 2, 2013

Copyright © 2013 Gary Bedingfield (Baseball in Wartime). All Rights

Reserved.

Steve

Sakas

Steve

Sakas Steven

P. “Steve” Sakas was born in

Steven

P. “Steve” Sakas was born in

Sakas

only spent a short time with

Sakas

only spent a short time with